Mark Steinberg’s conventional academic biography describes his work on histories of labor relations, cities, revolution, popular culture, religion, and emotions among other questions. Titles of his chapters and books on Russian history suggest something of his preoccupations and approach: “moral communities,” “proletarian imagination,” “knowledges of self,” “modernity and its discontents,” “feelings of the sacred,” “streets,” “masks,” “death,” “happiness,” “melancholy,” “utopians.”

Mark Steinberg’s conventional academic biography describes his work on histories of labor relations, cities, revolution, popular culture, religion, and emotions among other questions. Titles of his chapters and books on Russian history suggest something of his preoccupations and approach: “moral communities,” “proletarian imagination,” “knowledges of self,” “modernity and its discontents,” “feelings of the sacred,” “streets,” “masks,” “death,” “happiness,” “melancholy,” “utopians.”

If there is a consistent thread here, besides Russian history, it are the efforts (unrealizable, even hubristic) to both recover human “experience” in all its complexity, depth, ambiguity, and vitality and to reach beyond particular stories of the past toward questions of human existence and meaning. Woven through this is a persistent concern with the characteristically modern problem of a reality always simultaneously “delightful” and “dreadful,” as this contradiction and ambiguity has been famously summarized. This is a model, in all its elusiveness, for understanding Russian history but also perhaps for understanding our own place and work in the world.

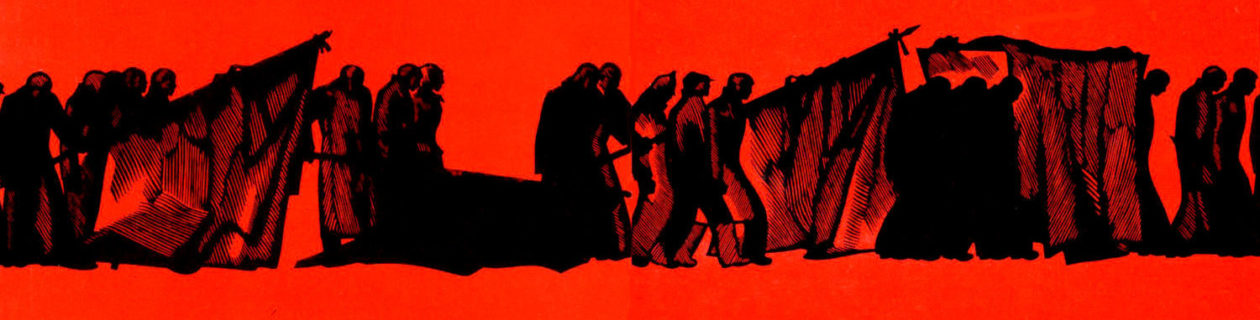

As the centenary of 1917 approached, but also the 500th anniversary of More’s Utopia (1516), and thinking about our own times of deepening danger and catastrophe and of growing if feeble resistance, Steinberg has been involved (often as organizer) with a series of programs around the questions of utopia and revolution as topics and methods of exploring history. Inspired by the work of Ernst Bloch and others who have rethought utopia (notably Fredric Jameson, Jose Munoz, Ruth Levitas), Steinberg has been worrying about our easy disenchantment with the outcomes of 1917 (violence, dictatorship, homogeneity, indignity, dehumanization), and of most other revolutions, and what this says about how we think about time, history, disaster, and possibility. If we are not to despair in the face of reality, what is to be done?

Representative publications:

Moral Communities: The Culture of Class Relations in the Russian Printing Industry, 1867-1907 (California 1992)

The Fall of the Romanovs: Political Dreams and Personal Struggles in a Time of Revolution, with Vladimir Khrustalev (Yale 1995)

Voices of Revolution, 1917 (Yale 2001)

Proletarian Imagination: Self, Modernity, and the Sacred in Russia, 1910-1925 (Cornell 2002);

Petersburg Fin-de-Siecle (Yale 2011)

The Russian Revolution, 1905-1921 (Oxford 2017) and a Russian translation published in Moscow in January 2018.

A History of Russia, with Nicholas Riasanovsky (9th edition: Oxford, 2018)

You must be logged in to post a comment.